Musik und Gesellschaft

Prepared by Peter Sühring

Online only (2020)

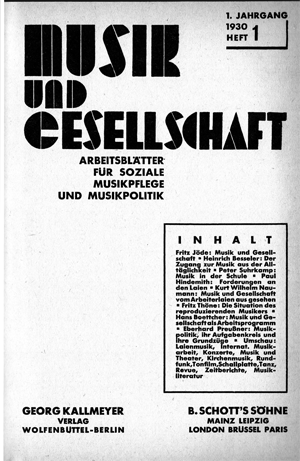

Musik und Gesellschaft: Arbeitsblätter für soziale Musikpflege und Musikpolitik (Music and Society: Worksheets for Social Music Care and Music Policy, RIPM code MGS) was published from April 1930 to February 1931 by Georg Kallmeyer in Wolfenbüttel/Berlin and by B. Schott's Söhne in Mainz. A total of eight issues were produced with dates of April, May, July, August, October, and November 1930 and January and February 1931. Each issue centered around a theme with the principal articles addressing aspects of the topic. The topics addressed were these: The Question of Music and Society (issue no. 1), Music and Work (no. 2), Music in the City, the Town, in the Countryside and in the Village (no. 3), The Musical Theater (no. 4), The Musical Laity Game (no. 5), The Piano Exercise (no. 6, supplemented with the Andante from Stravinsky’s Cinq Pièces faciles pour piano à quatre mains), Concert and Opera (no. 7), The Folk Song (no. 8).

The "discussion" section, which opens the second part of each issue, was devoted topics such as the impact of music in the industrialized work process and the importance of teaching pieces, especially new forms of music theater for the laity, following a performance review of the teaching piece Der Jasager of Berthold Brecht and Kurt Weill given at the Berlin-Neuköllner Karl Marx School. The rubric "The state of music in foreign countries" (in issues 3 to 7) included reports from Italy, America, Russia, England, Denmark and France. Under the rubric "Umschau" different issues were discussed, including amateur music, international music work, musical vocational questions, vocational education, concert, music and theater, university and college, appointments, church music, music industry, radio, sound film, records, musical revues, and dance. Within these headings there were the following subheadings: organizational, statistical, social, and political. The section "Zeitberichte" was mainly devoted to correspondence concerning workshops for amateur, folk and youth music. Reviews were divided into the following subheadings: musicology, male choir, music sociology, musical ethnography, instruments of domestic and youth music, monography, church music, music history, music theory, choral music, folk dance, sound film and records. An unpaginated section of advertisements from various publishers concluded issues, usually some 10 pages. Each issue contained a total of 32 pages, with one exception, the first issue with 40 pages. The main articles, contributions to the discussion and the reports from abroad were printed in single column format while the contributions to the sections Zeitberichte, Umschau and Musikliteratur were printed in two columns.

Musik und Gesellschaft appeared at the height of the Great Depression, in which bourgeois musical life in Germany faced economic problems, generating a desire for forms of music practice which were less costly and less socially restricted than concerts and opera. For many, the separation between musicians and passive listeners and the exclusion of the lower strata of society from the musical life was perceived as abhorrent. The advance of mechanically reproduced music through records, radio and film was also a major theme, as it was seen as a danger, further diminishing independent music making as a valuable expression of human life. Topics related to these phenomena – especially state, public and private music education and the commercialization of the music business – were discussed in the journal. The goal of those associated with MGS was to provide musical and sociological findings and interpretations and to discuss them in close connection with practical musicians.

The MGS reflects the “Jugendbewegung” (youth movement) tradition, whose musical initiatives were shaped by young song and music circles, completely outside of bourgeois cultural institutions. The ideological center of this movement was the idea of community, specifically the value of commonality in music making, with the organizational expression of this movement being the “Musikergilde” (musicians guild) and expressed with a patina of natural-mystical, Nordic-“völkisch” aspects. However, at the end of the twenties, those in this movement were forced to confront other anti-bourgeois currents of new musical practices coming from the workers' movement. The founding of “Volksmusikschulen” (folk music schools) sponsored by the Prussian state in the working class districts of Berlin and the dedication of certain composers to work with and for groups of lay musicians led to a second socio-politically oriented music movement to which the youth music movement intended to build a bridge. From this situation Musik und Gesellschaft was born and conflicts inherent between these movements prevented a longer publication run.

This bridge was expressed in the co-editorship of Fritz Jöde as a representative of the youth movement and Hans Boettcher as head of the folk music school of Berlin-Neukölln. MGS’s double-publishing arrangement functioned similarly, with the Georg Kallmayer Verlag acting on behalf of the youth movement and Schott-Verlag staning for modern composers and new forms of musical life. Not long after beginning publication, Jöde left the editorship and Boettcher largely retired from the editorial work; thereafter the magazine developed into an open, democratically debating body, quite in the sense of the subtitle’s description of each issue as “worksheets.” Musik und Gesellschaft brought together various artistic, scholarly and political initiatives whose common goal was to provide a musical life in which all people could participate, in other words, an essentially democratic musical culture. Impulses emanating from contemporary “Lebensphilosophie” (philosophy of life) and “Existenzphilosophie” (existentialism), complete with their catchphrases of communal and existential music making, were regularly confronted with references to unresolved problems of social existence where people are distant from music and trapped in work. The relatively early end of this cooperation between the movements shows this confrontation could not in the long run lead to any bridging and ideologically-free, discussable working atmosphere.

These music-sociologically oriented debates were later integrated into the journal Melos, while the youth music movement created its own organs again and was finally brought under the yoke of the National Socialists in 1933, at which time the sociology of music associated with the workers' movement was banned and its representatives expelled. In almost all contributions in Music und Gesellshaft, sympathy for the communitarian idea and for notions of the state as an organism controlling everything is noticeable in questions of music and society. Only rarely do voices of warning rise, either from reactionaries or from others on the political left. An example of journal’s vulnerability to dictatorial models can be found in the Italian report by Hans Hartmann in the third issue.

Editors

Fritz Jöde (1887-1970)

Music teacher and pedagogue, leader of youth music groups, Jöde taught and practiced in Hamburg, Berlin, Munich, Salzburg, and after 1945 in Bad Reichenhall and Hamburg. A leading representative of the German youth music movement, he was a theoretical and practical representative of the collective musical and public singing practice. After 1933, he adapted to National Socialism. In MSG, he published only the introductory policy article, in which music he called for music to be a community-founding element for the building of people and the state.

Hans Boettcher (1903-1945)

A musicologist and educator, Boettcher was head of a folk music school in Berlin-Neukölln co-founded with Kurt Löwenstein and Leo Kestenberg. He founded and directed a working group in music sociology. Boettcher collaborated with music teachers and students of the Neuköllner Karl Marx School. After disputes with the reactionary forces in the youth music movement, he became head of sociology of music department in the journal Melos. Relieved of his office in 1933, he was arbitrarily shot in the last days of the Second World War. His focus was on those making music, not the music itself. In MGS, he wrote the second principle article on music and society as a work program in which he developed questions and methods of investigation. In addition, he contributed a report on new music in Berlin.

Ernst Emsheimer (1904-89)

A musicologist, ethnomusicologist and instrument historian, Emsheimer studied in Frankfurt am Main, Vienna, and he had completed a doctorate with Wilibald Gurlitt in Freiburg. He was active in early 1930s Berlin in the Social Democratic “Kinderfreunde-Bewegung” (friends of children movement). In 1932 he moved to Leningrad where he was employed by the Music Ethnographic Institute. He fled from the Stalinist purges, and deprived of German citizenship he settled in Stockholm where he initially worked as an employee in the Ethnomusicological Institute, later becoming director of the Museum of Music History until 1983. In MGS he moderated and commented on discussions on the use of music, especially of workers' songs in the production process, e.g. „Mechanischer Arbeitsvollzug – Arbeitslied ‑ Freizeit“ (Mechanical execution ‑ work song ‑ free time) and "Stand der Diskussion – Ansätze zu neuer Fragestellung?” (State of the discussion ‑ approaches to new clear question?). A rather basic article in MGS shows Emsheimer’s proximity Hans Boettcher’s conceptions: "Die soziale Bedeutung der Musik im proletarischen Werktag” (The Social Meaning of Music in the Proletarian Workday). In addition, he displayed a fascination with jazz in Paris while his discussion of a new edition of the organ works of Michael Praetorius displayed his concerns for historicism.

Manfred Bukofzer (1910-55)

A musicologist, Bukofzer studied in Heidelberg and Berlin and received his doctorate in Switzerland. While in Berlin, he was in close contact with musicians who members of, of close to, the Communist Party. He went to the United States in 1936 and taught baroque music at the University of California, Berkeley until his untimely death. In MGS he published a central contribution to the discussion on work and music and the importance of the Lehrstück (teaching piece) “Zur Frage nach der Wirklichkeit des Musizierens. Was heißt es, die Existenz in das Musizieren hineinstellen?” (On the question of the reality of making music. What does it mean to put existence into music making?) and a report on a discussion evening about music in the “Volkshochschule” (community college) "Zur Soziologie der Volksmusikerziehung. Colloquium in der Deutschen Hochschule für Politik” (The Sociology of Folk Music Education, Colloquium in the German University of Politics).

Contributors

‑ Julius Bab (1880-1955), dramatist and theater critic, a representative of the Volksbühnenbewegung, and director of the theater division of the Jewish Cultural Association until 1938, he later emigrated to the US. In MGS he published an excerpt from his book The Theater in the Light of Sociology (1931) on the social function of the audience in theaters.

‑ Paul Bekker (1882-1937), a conductor, director and music historian, emigrated via Paris to the United States in 1933. Bekker provided the MGS with an excerpt on the "crisis of the opera theater" from his book Das Operntheater (1931).

‑ Heinrich Besseler (1900-1969), a musicologist focused on medieval music, published an excerpt on "The Access to Music from the Everyday" from his Freiburg habilitation lecture on musical hearing.

‑ Rudolf Bilke, a school musician and music critic, published a statement in MGS on music education and politics.

‑ Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), German poet and playwright, later exiled in Denmark, Finland and the USA. For MGS he published the first print of his basic commentary on opera: "On the sociology of opera. Notes to Mahagonny,” which he later incorporated into the complete edition of his essays. His works were regularly discussed in MGS, especially his teaching piece for pupils from Berlin – Der Jasager, Der Neinsager (with music by Kurt Weill) – and The Measure or Die Maßnahme (with music by Hanns Eisler).

‑ Heinz Edelstein (1902-1959), a pupil of the Odenwald School, Edelstein emigrated to Iceland where he built music schools. For MGS he wrote two articles, one on sociological questions and the other on the folk song movement.

‑ Hans Engel (1894-1970), a musicologist and conductor, Engel taught in Greifswald, Königsberg and Marburg and he discussed musical-sociological questions before and after 1933. For MGS he contributed "Rhythm of Time" and a report on the folk music and singing school conference in Bochum-Essen, 1930.

‑ Hermann Erpf (1891-1969), a music pedagogue and composer, Erpf was a representative of the youth music movement and taught from 1935 at the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen and at the Musikhochschule in Stuttgart where he was director from 1943-1945 and 1952-1956. In MGS he published a report from the folk music and singing school conference in Bochum-Essen, 1930.

‑ Otto Johannes Gombosi (1902-55), a Hungarian musicologist who studied in Berlin, later teaching and researching in Basel, Bern, Chicago and Boston. For MGS wrote he wrote a treatise on the emergence of folk songs and a review of Edwin van der Nüll’s book on Béla Bartók.

‑ Hans Hartmann. Wrote a report on contemporary Italian music for MGS as part of the series “The Musical Situation in Foreign Countries” with unmistakable sympathy for fascist state music policy.

‑ Hermann Heiß (1898-1966) studied in Vienna, Frankfurt and Berlin and was a composer and music teacher at the reform school Hermann Lietz on Spiekeroog (1928-1933) and after 1945 as a teacher of twelve-tone and electronic music. For MGS, Heiß contributed articles on pedagogy and the creative musicians.

‑ Paul Hindemith (1895-1963), a composer, participated in experiments with lay musicians at the beginning of the 1930s about which he contributed an article in the first issue. In almost all issues of the MGS Brecht and Hindemith’s Badener Lehrstück vom Einverständnis (Baden teaching piece of consent) is presented as a model alongside Hindemith’s so-called Spielmusiken and works for male choirs.

‑ Herbert Just, composer and music teacher, wrote two conference reports in the MGS on Baroque musical instruments and the conference of German Musicians and Music Teachers.

‑ Erich Katz (1900-1973), a composer and music educator, studied in Berlin and Freiburg where he created the Freiburger Volksmusikhochschule and courses in music theory. He later emigrated via England to the USA and became a music professor in New York and Santa Barbara. A representative of the singing and recorder movement, he wrote three reviews on related topics in MGS.

‑ Gerhard Kowalewsky, by profession a metalworker in a large business, contributed reports on the industrial world of work and the possibility of music use in the factories. He also reviewed the music for Eisenstein’s film The General Line.

‑ Ernst Křenek (1900-91), a composer, lived in Vienna and Berlin and after 1938 in the USA. He contributed a review for MGS and was frequently cited.

‑ Martin Luserke (1880-1968), a reform educator, singer and playwright, he taught at school communities in Wickersdorf and Juist. For MGS he wrote for on music and amateur theater (together with Eduard Zuckmayer).

- Eberhard Preußner (1899-1964), a music educator, he worked in Berlin and Salzburg with Leo Kestenberg, later becoming a member of the Reichsmusikkammer and from 1928-1944 editor of the NS journals Die Musik und Die Musikpflege. He was later associated with the Mozarteum in Salzburg, becoming president in 1959 and director of the Salzburg Festival in 1960. For MGS he wrote on music policy, politics and a review of the Leipzig premiere of Brecht and Weill’s opera Mahagonny.

‑ Curt Sachs (1881-1959), music historian and instrumentalist, contributed a review.

‑ Charlotte Schlesinger (1909-1976), a pupil of Schreker and Hindemith, was a composer and music pedagogue and worked in Berlin, Kiev and the United States. In the MGS she published a report on musical-educational games for children.

‑ Rudolf Sonner, a music educator and music writer, was a proponent of National Socialism and propagandist of Wagner. In MGS he wrote on metropolitan music consumers and contributed two reviews.

‑ Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), composer, wrote on the lack of appreciation for his music. His works are constantly referenced in the MGS issues, for example, his Cinq Pièces faciles for piano à quatre mains are discussed as example works.

‑ Peter Suhrkamp (1891-1959) worked as a teacher in the field of reform education and as a journalist and publisher. In MGS he wrote on school music and a report on the production of sound film by Brecht and Weill.

‑ Gertrude Trede (1901-?), a musician who later fled to England, wrote for MGS on four-handed piano playing.

‑ Hilmar Trede (1902-?), a musicologist wrote with Hans Boettcher a principle article on the Lehrstück (teaching piece) and reviews.

‑ Wilhelm Twittenhoff (1904-1969), a private music teacher and instructor for teachers of folk and youth music schools, worked with Carl Orff and assumed leading activities for the National Socialist youth music policy. After 1945 he contributed to the development of folk and youth music schools. In MGS he published on music in the country and "Teaching - Enjoyment - Illusion - Virtue - Knowledge.”

‑ Walter Wiora (1906-97), a music historian and folk song researcher, was a staff member of the Freiburger Volksliedarchiv (archive of folk songs) in the 1920s and 1930s and held professorships in Poznan, Kiel and Saarbrücken after the war. He contributed to the NS-journals Die Musik and Das Reich. For MGS he wrote reviews of sociological publications.

This RIPM Index was produced from a reprint of the magazine edited by Dorothea Kolland and published by the West Berlin publishing house das europäische buch (deb) in 1978.