The Metronome

Prepared by Vashti Gray Sadjedy and Richard Kitson

Online only (2011)

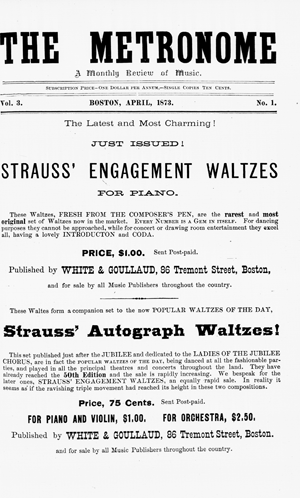

The Metronome: A Monthly Review of Music [MET] was published monthly in Boston from April 1871 to May 1874 by White and Goullaud. Each issue consists of eight to ten pages of articles and four pages of advertisements, preceding and concluding each issue. A typical issue commences with a lengthy article dealing with the training of the voice by Dr. H. R. Streeter, followed by several short articles and reviews about recent or forthcoming musical events in Boston and other American cities; and complete articles and extracts taken from English journals (The Athenæum and The Musical World), and from the principal American newspapers and magazines. The second half commences with repetition of the journal’s title, names of editors, the date of the current issue and an editorial, and continues with longer articles addressing local performance practice, reviews of musical events, and a concludes with a miscellaneous section containing news and gossip about musicians.

During its three years of publication, MET was edited by Ambrose Davenport, Jr. and Warren Davenport, professionally known as the Davenport Brothers, who wrote all of the journal’s articles that are not explicitly attributed to other authors. Ambrose Davenport, Jr. was a music engraver and a composer and arranger of music for violin (an arrangement for violin and piano of Hermann Fliege’s Chinese Serenade (1885) and an original Easter anthem entitled “Christ our Passover”). He translated Louis Schubert’s text, Violin School, published in 1887. In 1888 he became editor of the widely circulated Boston music journal The Folio (1869-1895). His brother, Warren Davenport, was an active music critic and frequently contributed his writings to The Folio, the Boston Herald, the Daily Traveller, and Musical America.

The editors’ determination “to speak of artists and composers in their professional capacity just as [they] find them” became a hallmark of the journal. Brutally honest reviews were routinely published, to such an extent that the editors repeatedly complained in later issues of being denied press tickets for Boston concerts because of their growing reputation for scathing criticisms. The Davenport Brothers were strong advocates for the development of uniquely American music, and encouraged the development of more American composers while discouraging the widely-held impression that a musical education was incomplete without study in Europe. However, they did not hesitate to bestow harsh criticism on mediocre musicians and music educators, and firmly advocated that the highest standards must be upheld if the United States was to be established as a musical and cultural center of importance.

Notable among the contents are extensive discussions of the American premieres of John Knowles Paine’s oratorio, St. Peter, W. J. D. Leavitt’s oratorio, The Coronation of David, and the long-overdue Parisian premiere of Handel’s Messiah. Other reviews include the concerts of the Thomas Orchestra, the New England Conservatory of Music, the Parepa-Rosa, the Nilsson-Strakosch, the Pauline Lucca and the Max Maretzek opera troupes, the Dolby ballad concerts, the Harvard Musical Association concerts, pianist Carlyle Petersilea’s Beethoven sonata recitals, and the American appearances of violinists Pablo de Sarasate and Henri Wieniawski, pianists Benjamin Johnson Lang and Anton Rubinstein, contralto Carlotta Patti and the concerts of the Foster Club (a choral society). Two extensive articles published in July and August 1872 review the International Festival and Peace Jubilee held in Boston. Scathingly critical articles discuss soprano Christine Nilsson’s musical and moral deficiencies, and numerous columns denigrate the lack of musical ability and narrowness of repertory of the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston. Unusual is the harsh criticism written about the competing music periodical Dwight’s Journal of Music, in which the Davenport Brothers disparage the editor John Sullivan Dwight’s “sentimental prose” and “lack of formal musical education,” and similar negative opinions about the Boston pianist Otto Dressel and conductor Carl Zerrahn. Also included are biographical sketches of many composers and performers.